Junction Trio

Stefan Jackiw, violin; Jay Campbell, cello; Conrad Tao, piano

Cookie Notice

This site uses cookies to measure our traffic and improve your experience. By clicking "OK" you consent to our use of cookies.

Junction Trio combines three game-changing musicians’ talents into one sensational and eclectic group. This “spectacularly talented” (SeenandHeard International) all-star trio derives its name from its members’ initials: J – C – T.

Each artist has appeared previously on the Series in an unexpected pairing, and the trio’s program for this concert interweaves the old and the new in surprising and illuminating ways: arrangements of Renaissance madrigals and trios by Ravel and Schumann sit alongside a Celebrity Series co-commission, Bells and Whistles by Amy Williams.

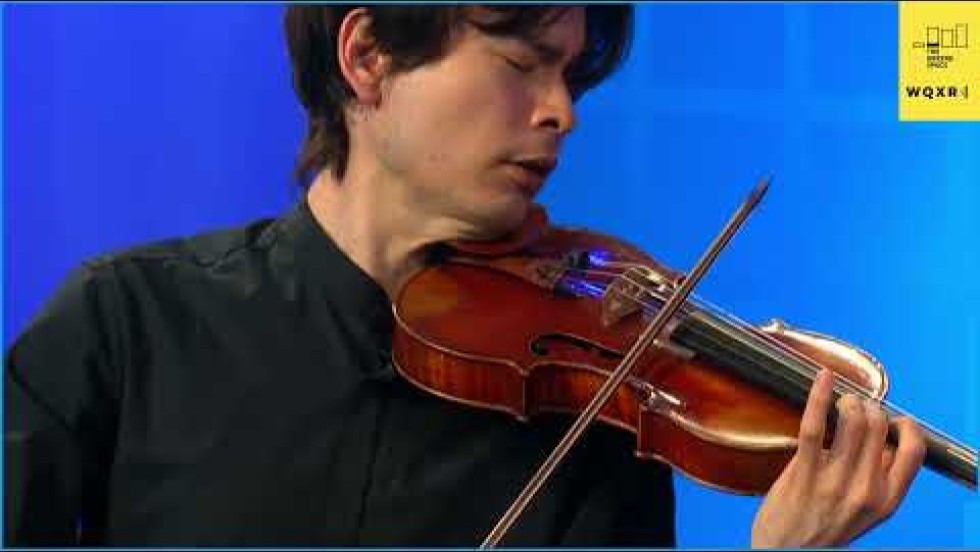

J stands for violinist Stefan Jackiw, who most recently appeared with Celebrity Series alongside pianist Jeremy Denk for a deep dive into the violin sonatas of Charles Ives.

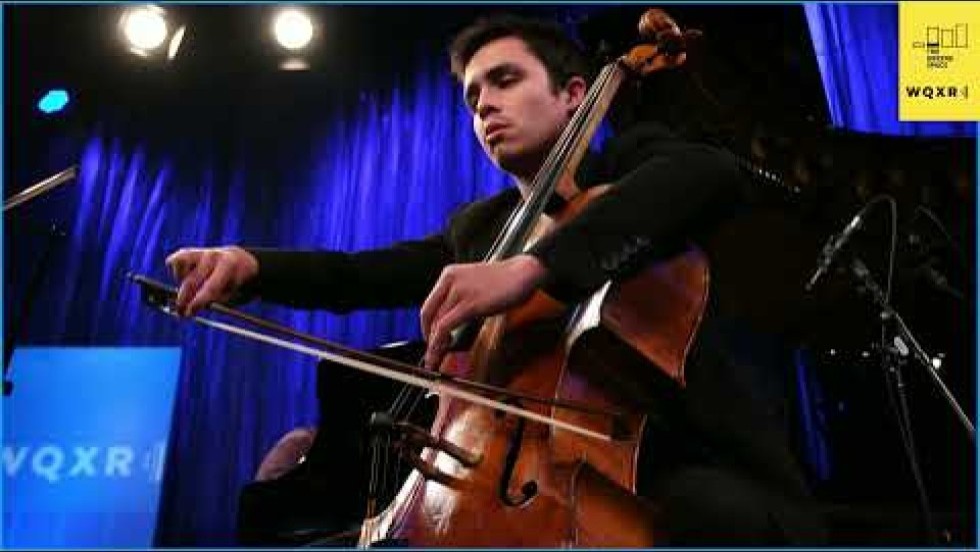

C is for cellist Jay Campbell, last heard by Celebrity Series audiences in an unconventional but acclaimed pairing with violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja in the 2019/20 season.

T represents pianist Conrad Tao, heard most recently in 2021 in his celebrated Boston solo recital debut at Pickman Hall. Tao made his Series debut with dancer Caleb Teicher in More Forever, and has been dubbed a musician of “probing intellect and open-hearted vision” by the New York Times.

Audiences around the country have been thrilled by this amazing trio of friends and collaborators, and we can’t wait to share their artistry with you!

Program Details

Amy Williams is a composer of music that is “simultaneously demanding, rewarding and fascinating” (Buffalo News), “fresh, daring and incisive” (Fanfare). Her compositions have been presented at renowned contemporary music venues in the US, Australia, Asia, and Europe by leading contemporary music soloists and ensembles, including the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, JACK Quartet, Ensemble Musikfabrik, Wet Ink, Talujon, International Contemporary Ensemble, h2 Saxophone Quartet, Bent Frequency, pianist Ursula Oppens, soprano Tony Arnold, and bassist Robert Black. Her pieces appear on the Albany, Parma, VDM (Italy), Blue Griffin, Centaur, and New Ariel labels. As a member of the Bugallo-Williams Piano Duo, Ms. Williams has performed throughout Europe and the Americas and recorded six critically-acclaimed CDs for Wergo (works of Nancarrow, Stravinsky, Varèse/Feldman and Kurtág), and also on the Neos and Albany labels. Ms. Williams has been awarded a Howard Foundation Fellowship, Fromm Music Foundation Commission, Guggenheim Fellowship, Koussevitzky Music Foundation Commission, Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Fulbright Scholars Fellowship to Ireland (2017/18). Ms. Williams holds a PhD in composition from the University at Buffalo, where she also received her Master's degree in piano performance. She has taught at Bennington College and Northwestern University and is currently Associate Professor of Composition at the University of Pittsburgh. She is Artistic Director of the New Music On The Point Festival in Vermont. The composer provided this note on the piece performed today:

The term “bells and whistles” comes from the fairground organ and also from early 20th-century “master” clocks, which could operate different clocks throughout a factory or school to ring bells or blow whistles. These sonic images are combined with other types of bells (fire alarms, train whistles, bell towers, cuckoo clocks, anvils). The piece is in three continuous sections—the first is focused on clocks (mechanical, ticking sounds), the second on (fast, driving) trains, and the third on (ringing, accumulating) bells. Bells and Whistles was co-commissioned by the Denver Friends of Chamber Music and the Celebrity Series of Boston for the Junction Trio.

Amy Williams is a composer of music that is “simultaneously demanding, rewarding and fascinating” (Buffalo News), “fresh, daring and incisive” (Fanfare). Her compositions have been presented at renowned contemporary music venues in the US, Australia, Asia, and Europe by leading contemporary music soloists and ensembles, including the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, JACK Quartet, Ensemble Musikfabrik, Wet Ink, Talujon, International Contemporary Ensemble, h2 Saxophone Quartet, Bent Frequency, pianist Ursula Oppens, soprano Tony Arnold, and bassist Robert Black. Her pieces appear on the Albany, Parma, VDM (Italy), Blue Griffin, Centaur, and New Ariel labels. As a member of the Bugallo-Williams Piano Duo, Ms. Williams has performed throughout Europe and the Americas and recorded six critically-acclaimed CDs for Wergo (works of Nancarrow, Stravinsky, Varèse/Feldman and Kurtág), and also on the Neos and Albany labels. Ms. Williams has been awarded a Howard Foundation Fellowship, Fromm Music Foundation Commission, Guggenheim Fellowship, Koussevitzky Music Foundation Commission, Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Fulbright Scholars Fellowship to Ireland (2017/18). Ms. Williams holds a PhD in composition from the University at Buffalo, where she also received her Master's degree in piano performance. She has taught at Bennington College and Northwestern University and is currently Associate Professor of Composition at the University of Pittsburgh. She is Artistic Director of the New Music On The Point Festival in Vermont. The composer provided this note on the piece performed today:

The term “bells and whistles” comes from the fairground organ and also from early 20th-century “master” clocks, which could operate different clocks throughout a factory or school to ring bells or blow whistles. These sonic images are combined with other types of bells (fire alarms, train whistles, bell towers, cuckoo clocks, anvils). The piece is in three continuous sections—the first is focused on clocks (mechanical, ticking sounds), the second on (fast, driving) trains, and the third on (ringing, accumulating) bells. Bells and Whistles was co-commissioned by the Denver Friends of Chamber Music and the Celebrity Series of Boston for the Junction Trio.

Maurice Ravel was the son of a distinguished inventor-engineer, who, in 1868, devised a self-propelled, steam-powered vehicle that ran for hours in the streets of Paris and, in the 1870s, was instrumental in building the railroads of Spain. While working in Spain, Ravel’s father married a Basque woman, but Maurice, his first son, was born on the French side of the nearby frontier. A few months after his birth, the family returned to Paris, where Ravel would begin his musical studies at the age of seven. At eighteen, he began to write music, and, at twenty, he was a published composer.

Ravel was always attached to the region of his birth; in 1914, he returned there to spend the summer. He was staying at Saint-Jean-de-Luz and working on his Piano Trio when the outbreak of war suddenly changed his plans. He decided to volunteer for military service despite his physical frailty and rushed to finish the composition. “I am working with the sureness and the lucidity of a madman,” he wrote to some friends, “but as I work, something gnaws at me, and suddenly I find myself sobbing over my music.” The trio was first performed on January 28, 1915, in Paris. The Italian composer Alfredo Casella played the piano part, Gabriel Willaume the violin, and Louis Feuillard, the cello, but as Paris was preoccupied with political troubles then, the important premiere was hardly noticed. The trio was published that same year with a dedication to André Gédalge, a theoretician and a teacher to whom Ravel and generations of American and French composers owed much of their technical skill.

The broad and powerful Piano Trio is a serious work, firm in structure, written in cool but brilliant colors skillfully extracted from the contrasting sonorities of the piano and the strings. Ravel’s biographer, Stuckenschmidt, described it as presenting “almost orchestral effects—because Ravel spreads the construction over the many different registers of the three instruments.”

The first movement, Modéré, which Ravel described as Basque in character, is based on folk materials that he had originally intended to use in a piano concerto. The gentle, swaying opening subject supplies many elements Ravel returned to in the later movements. He drew its compound rhythm (3-2-3) from a Basque folk dance. The violin and cello articulate accents in different places, giving the movement a highly individual sound. The cello keeps the familiar and steady four beats of the meter, while the violin divides the eight possible eighth notes of these four beats into three-plus-two-plus-three, in an off-beat rhythm associated with Basque music. The violin’s part in this movement is virtuosic.

The vivacious second movement is a scherzo, Assez vif, called a pantoum, the name of a verse form of Malaysian origin that the 19th-century French Romantic poets, Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire, took up for its exotic flavor. A pantoum is a poetic structure in which two ideas or two pairs of a rhyme-scheme interlock. Specifically, in the poetic pantoum, made up of a group of quatrains, (four-line stanzas), each new quatrain repeats as its first and third line the second and fourth line of the preceding one. Ravel’s two musical themes echo that poetic form in the way they alternate and are interwoven.

Passicaille, or passacaglia, the slow movement, Très large, consists of a series of continuous variations on a single phrase of broad melody in a form Bach made famous. Interestingly enough though, the passacaille did originate in Spain with the pasacalle, where a four-bar bass ostinato was the basis for sets of variations. Here Ravel uses an eight-measure theme that begins in the bass and becomes the subject of ten variations. As the variations progress, the tension increases, first with a crescendo and a rise from low to high register, and then after the climactic center of the movement, a diminuendo and a gradual return to the lower bass register, bringing a sense of relaxation. This movement runs without pause into the brilliant Final, Animé, whose main theme is constructed on an inversion of the first theme of the initial movement. Here again the listener is aware of Ravel’s aggressively bold rhythm of mixed meters.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

.

Maurice Ravel was the son of a distinguished inventor-engineer, who, in 1868, devised a self-propelled, steam-powered vehicle that ran for hours in the streets of Paris and, in the 1870s, was instrumental in building the railroads of Spain. While working in Spain, Ravel’s father married a Basque woman, but Maurice, his first son, was born on the French side of the nearby frontier. A few months after his birth, the family returned to Paris, where Ravel would begin his musical studies at the age of seven. At eighteen, he began to write music, and, at twenty, he was a published composer.

Ravel was always attached to the region of his birth; in 1914, he returned there to spend the summer. He was staying at Saint-Jean-de-Luz and working on his Piano Trio when the outbreak of war suddenly changed his plans. He decided to volunteer for military service despite his physical frailty and rushed to finish the composition. “I am working with the sureness and the lucidity of a madman,” he wrote to some friends, “but as I work, something gnaws at me, and suddenly I find myself sobbing over my music.” The trio was first performed on January 28, 1915, in Paris. The Italian composer Alfredo Casella played the piano part, Gabriel Willaume the violin, and Louis Feuillard, the cello, but as Paris was preoccupied with political troubles then, the important premiere was hardly noticed. The trio was published that same year with a dedication to André Gédalge, a theoretician and a teacher to whom Ravel and generations of American and French composers owed much of their technical skill.

The broad and powerful Piano Trio is a serious work, firm in structure, written in cool but brilliant colors skillfully extracted from the contrasting sonorities of the piano and the strings. Ravel’s biographer, Stuckenschmidt, described it as presenting “almost orchestral effects—because Ravel spreads the construction over the many different registers of the three instruments.”

The first movement, Modéré, which Ravel described as Basque in character, is based on folk materials that he had originally intended to use in a piano concerto. The gentle, swaying opening subject supplies many elements Ravel returned to in the later movements. He drew its compound rhythm (3-2-3) from a Basque folk dance. The violin and cello articulate accents in different places, giving the movement a highly individual sound. The cello keeps the familiar and steady four beats of the meter, while the violin divides the eight possible eighth notes of these four beats into three-plus-two-plus-three, in an off-beat rhythm associated with Basque music. The violin’s part in this movement is virtuosic.

The vivacious second movement is a scherzo, Assez vif, called a pantoum, the name of a verse form of Malaysian origin that the 19th-century French Romantic poets, Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire, took up for its exotic flavor. A pantoum is a poetic structure in which two ideas or two pairs of a rhyme-scheme interlock. Specifically, in the poetic pantoum, made up of a group of quatrains, (four-line stanzas), each new quatrain repeats as its first and third line the second and fourth line of the preceding one. Ravel’s two musical themes echo that poetic form in the way they alternate and are interwoven.

Passicaille, or passacaglia, the slow movement, Très large, consists of a series of continuous variations on a single phrase of broad melody in a form Bach made famous. Interestingly enough though, the passacaille did originate in Spain with the pasacalle, where a four-bar bass ostinato was the basis for sets of variations. Here Ravel uses an eight-measure theme that begins in the bass and becomes the subject of ten variations. As the variations progress, the tension increases, first with a crescendo and a rise from low to high register, and then after the climactic center of the movement, a diminuendo and a gradual return to the lower bass register, bringing a sense of relaxation. This movement runs without pause into the brilliant Final, Animé, whose main theme is constructed on an inversion of the first theme of the initial movement. Here again the listener is aware of Ravel’s aggressively bold rhythm of mixed meters.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

.

The Italian composer and lutenist Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, composed extraordinary music, extending tonality and chromaticism to its limits, a practice not again developed with such intensity until the 20th century. (Interestingly, Gesualdo was one of Stravinsky’s favorite composers.) Gesualdo was known as the arch-chromaticist of the late Renaissance. Because of his use of dazzling harmonic shifts in his books of madrigals, his music was thought so extreme that some 20th-century critics ventured the theory that he had journeyed farther than any composer before Schoenberg in exploring and using expressive dissonance. Musicologist Glenn Watkins commented that Gesualdo’s music has enthralled and inspired 20th- and 21st-century composers from Stravinsky to Boulez.

In 1590, after discovering that his wife, Donna Maria d’Avalos had been having a two-year affair, Gesualdo murdered her and her lover, the Duke of Andria. The crimes were documented in contemporary court records, which detail the events of the night of October 16, when Gesualdo, returning home unexpectedly from a hunting expedition, discovered the lovers and, with the aid of his servants, killed them in a frenzied attack. It is possible also that Gesualdo ordered the murder of his infant child, who he believed had a strong resemblance to the Duke; it is hypothesized that he had the baby’s cradle violently swung until the child expired. As a result of these actions, Gesualdo spent his final years in isolation and despair, but as a nobleman, he was immune from prosecution.

Over the centuries, Gesualdo’s fame relied chiefly on the notoriety of his dramatic, unhappy, and often bizarre life, but his reputation as a musician has more recently grown, based on his highly individual and richly chromatic madrigals. (A madrigal is a short secular piece for a small group of voices.) Gesualdo possibly wrote the poems for his madrigals himself or had them written specifically for him. The texts often focus on themes of torment, pain, sadness, and death. Gesualdo’s madrigals also are notable for their chromaticism, discontinuous texture, and experimental harmonic technique; in his polyphony, each voice has equal importance.

Toward the end of his life, Gesualdo composed the highly dramatic and moving Tenebrae Responsoria for Christian liturgical use during Holy Week. It was first published in 1611 as Part 1 of Responsoria et alia ad Officium Hebdomadae Sanctae spectantia. There were nine responsories in six parts each for Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, with psalms and canticle for lauds for each day. The text was derived from entire sections of the Passion according to St. Matthew and relevant Psalm verses.

Gesualdo actually published three sets of moving and very dramatic Tenebrae Responsoria. The Latin 'Tenebrae' variously means darkness, night, unconsciousness, death, blindness, obscurity, and even sometimes is used to suggest the underworld. 'Tenebrae' also refers to an office of the Christian church associated specifically with Holy Week. Taking place at night, the liturgy is characterized by the gradual extinguishing of candles, until the service ends in complete darkness.

The Tenebrae Responsoria combine a rich spirituality with more secular, madrigal-like features. The six-voice Responsoria display the dense, chromatic language of Gesualdo’s madrigals, here applied to sacred texts. Overall, they project an intense energy and combine contrasting styles and harmonies. Formally, these works are memorable for their expressiveness, which Gesualdo reinforced with his use of chromatic shifts, unusual tunings, and virtuosic leaps and runs. A distinctive feature of it is the inclusion of the Gregorian chants that, in the piece’s original vocal form, figured as a uniting feature for the roles the Evangelist, Jesus, and other characters sing. Gesualdo includes sinister harmonies which are utilized to create the feeling of the elders’ intentions to kill Jesus; in many places in the music Gesualdo has depicted emotions, like weeping and feelings of dejection. Slow modulations were intended to represent Jesus’ ultimate desolation.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

The Italian composer and lutenist Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, composed extraordinary music, extending tonality and chromaticism to its limits, a practice not again developed with such intensity until the 20th century. (Interestingly, Gesualdo was one of Stravinsky’s favorite composers.) Gesualdo was known as the arch-chromaticist of the late Renaissance. Because of his use of dazzling harmonic shifts in his books of madrigals, his music was thought so extreme that some 20th-century critics ventured the theory that he had journeyed farther than any composer before Schoenberg in exploring and using expressive dissonance. Musicologist Glenn Watkins commented that Gesualdo’s music has enthralled and inspired 20th- and 21st-century composers from Stravinsky to Boulez.

In 1590, after discovering that his wife, Donna Maria d’Avalos had been having a two-year affair, Gesualdo murdered her and her lover, the Duke of Andria. The crimes were documented in contemporary court records, which detail the events of the night of October 16, when Gesualdo, returning home unexpectedly from a hunting expedition, discovered the lovers and, with the aid of his servants, killed them in a frenzied attack. It is possible also that Gesualdo ordered the murder of his infant child, who he believed had a strong resemblance to the Duke; it is hypothesized that he had the baby’s cradle violently swung until the child expired. As a result of these actions, Gesualdo spent his final years in isolation and despair, but as a nobleman, he was immune from prosecution.

Over the centuries, Gesualdo’s fame relied chiefly on the notoriety of his dramatic, unhappy, and often bizarre life, but his reputation as a musician has more recently grown, based on his highly individual and richly chromatic madrigals. (A madrigal is a short secular piece for a small group of voices.) Gesualdo possibly wrote the poems for his madrigals himself or had them written specifically for him. The texts often focus on themes of torment, pain, sadness, and death. Gesualdo’s madrigals also are notable for their chromaticism, discontinuous texture, and experimental harmonic technique; in his polyphony, each voice has equal importance.

Toward the end of his life, Gesualdo composed the highly dramatic and moving Tenebrae Responsoria for Christian liturgical use during Holy Week. It was first published in 1611 as Part 1 of Responsoria et alia ad Officium Hebdomadae Sanctae spectantia. There were nine responsories in six parts each for Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, with psalms and canticle for lauds for each day. The text was derived from entire sections of the Passion according to St. Matthew and relevant Psalm verses.

Gesualdo actually published three sets of moving and very dramatic Tenebrae Responsoria. The Latin 'Tenebrae' variously means darkness, night, unconsciousness, death, blindness, obscurity, and even sometimes is used to suggest the underworld. 'Tenebrae' also refers to an office of the Christian church associated specifically with Holy Week. Taking place at night, the liturgy is characterized by the gradual extinguishing of candles, until the service ends in complete darkness.

The Tenebrae Responsoria combine a rich spirituality with more secular, madrigal-like features. The six-voice Responsoria display the dense, chromatic language of Gesualdo’s madrigals, here applied to sacred texts. Overall, they project an intense energy and combine contrasting styles and harmonies. Formally, these works are memorable for their expressiveness, which Gesualdo reinforced with his use of chromatic shifts, unusual tunings, and virtuosic leaps and runs. A distinctive feature of it is the inclusion of the Gregorian chants that, in the piece’s original vocal form, figured as a uniting feature for the roles the Evangelist, Jesus, and other characters sing. Gesualdo includes sinister harmonies which are utilized to create the feeling of the elders’ intentions to kill Jesus; in many places in the music Gesualdo has depicted emotions, like weeping and feelings of dejection. Slow modulations were intended to represent Jesus’ ultimate desolation.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

.Robert Schumann's father was a small‑town bookseller who encouraged his son's inclination toward the arts. At age six, the boy began to play the piano and to compose. By the time he was fourteen, he had become a published poet. At eighteen, he entered Leipzig University as a law student, but the call of music was too strong for him to resist; when he was in his third year, he left the University, determined to become a great pianist. It is unknown whether it was accident or illness that caused an injury to Schumann’s hand, but regardless, as a result of this injury, he suddenly gave up hope of a career as a performer, turned to composition, and wrote the several brilliant collections of short, descriptive, and atmospheric piano pieces that established his position as Germany's leading composer.

In 1838, Schumann wrote to Clara Wieck, who was later to be his wife, “The piano has become too limited for me.” He confided that he had begun working on ideas for string quartets. In 1839, he mentioned quartet writing again in letters to a friend and added that he was “living through some of Beethoven’s last quartets.” In 1840, the year of his marriage, he wrote almost nothing but songs, more than 130 of them, in a great outpouring of love. His attention was diverted to the orchestra in 1841, when he wrote four symphonic compositions and the first movement of his Piano Concerto.

In 1842, he finally put other work aside to concentrate on chamber music. That April, he ordered scores of all the Mozart and Beethoven quartets available and then studied them for two months. In a furious burst of creative energy between June and October, he composed three string quartets, a piano quartet, and a piano quintet.

It was not until 1847 that he wrote this, the first of his three trios for piano, violin, and cello. (He also wrote Op. 80, in F Major, in 1847 and completed Op. 11, in G minor, four years later in 1851.) Since piano was Schumann’s instrument of choice, he included the piano as part of his trio’s instrumentation. The work puts heavy emphasis on the piano with the stringed instruments acting together opposing the keyboard or even sometimes subsidiary to the piano as an element in what is a piano dominated texture. Schumann’s First Piano Trio is the most often performed of his three trios and the one historians and commentators have agreed is the strongest of the three.

The first movement, Mit Energie und Leidenschaft (“with energy and passion”) is thoroughly expansive and passionate. Written in contrapuntal sonata form in the minor tonality, it begins with a fervent violin theme. As Arthur Cohn comments, “Schumann, a fully developed romanticist at age 37, would not have much, if any, proportions to his themes; they were now the almost non-adhering, tonally swerving type.” Cohn also notes that Schumann made this movement quite chromatic in a Romantic style. The pianist plays rapid arpeggios throughout the first section to emphasize the harmony. The cello echoes fragments of the main theme, in free imitation.

Since Schumann clearly wished to attain rhythmic variety, he immediately presented the principal theme in three slightly different versions. The opening theme is an example of his new style of composing in which, according to the Grove Dictionary of Music, he demonstrates the “simultaneous development of motivic combinations.” In the contrasting second theme, the pianist plays the melody together with the strings, and when the second theme repeats, the violin and cello play in canon two octaves apart, following each a half measure apart. Near the exposition’s end, the main theme reappears combined with fragments of the second. During the development, Schumann introduces a new theme that has a distinctive melodic character and unusual scoring. This theme appears softly in the piano’s high range; Schumann directs the accompanying strings to play “am Steg” which means bowing the string as close as possible to the bridge. After repeating the new theme a few times, Schumann reverts back to the two themes from the exposition. In the recapitulation, the passionate energy returns, and the theme from the development makes its hushed appearance, too. Clara thought that this movement was the most beautiful of all the chamber music movements that Schumann composed.

The second movement, Lebhaft, doch nicht zu rasch (“lively, but not too fast”), is a fiery Scherzo and Trio in F major. The strings have a melody that rises energetically with a sort of perky quality. Listeners can discern that the distinctive long-short rhythmic motive was foreshadowed in the first movement. The Trio section, smoothly legato, uses canonic imitation between the piano and the strings, recalling the canon in the second theme of the first movement. The trio and the scherzo themes are actually both based on the same motive. The Scherzo theme returns, and then the movement concludes with a coda. In the deeply expressive yet relatively somber and concentrated third movement, Langsam, mit inniger Empfindungen, (“slowly, with inner feeling”) Schumann creates an expressive melodic theme and gives the whole a ternary form. The theme has a limitless, searching, syncopated line that moves from instrument to instrument with the piano often providing a rich and sometimes chromatic chordal support. A short transitional passage in the piano leads directly into the major tonality of the vibrant and strongly optimistic sounding rondo finale, Mit Feuer, (“with fire”). Here Schumann unites the trio’s movements by giving the piano the first four notes from the violin theme of the first movement, but in the finale, these notes are rhythmically altered. As the energetic movement progresses, the thematic utterances modulate through a highly unusual variety of keys. The cello announces the movement’s second theme. In the development, Schumann gives half his attention to the first theme, while he devotes the other half to the second. He then presents a short recapitulation and a rather lengthy coda, which speeds up in tempo as it brings the quartet to its brilliant end.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

.Robert Schumann's father was a small‑town bookseller who encouraged his son's inclination toward the arts. At age six, the boy began to play the piano and to compose. By the time he was fourteen, he had become a published poet. At eighteen, he entered Leipzig University as a law student, but the call of music was too strong for him to resist; when he was in his third year, he left the University, determined to become a great pianist. It is unknown whether it was accident or illness that caused an injury to Schumann’s hand, but regardless, as a result of this injury, he suddenly gave up hope of a career as a performer, turned to composition, and wrote the several brilliant collections of short, descriptive, and atmospheric piano pieces that established his position as Germany's leading composer.

In 1838, Schumann wrote to Clara Wieck, who was later to be his wife, “The piano has become too limited for me.” He confided that he had begun working on ideas for string quartets. In 1839, he mentioned quartet writing again in letters to a friend and added that he was “living through some of Beethoven’s last quartets.” In 1840, the year of his marriage, he wrote almost nothing but songs, more than 130 of them, in a great outpouring of love. His attention was diverted to the orchestra in 1841, when he wrote four symphonic compositions and the first movement of his Piano Concerto.

In 1842, he finally put other work aside to concentrate on chamber music. That April, he ordered scores of all the Mozart and Beethoven quartets available and then studied them for two months. In a furious burst of creative energy between June and October, he composed three string quartets, a piano quartet, and a piano quintet.

It was not until 1847 that he wrote this, the first of his three trios for piano, violin, and cello. (He also wrote Op. 80, in F Major, in 1847 and completed Op. 11, in G minor, four years later in 1851.) Since piano was Schumann’s instrument of choice, he included the piano as part of his trio’s instrumentation. The work puts heavy emphasis on the piano with the stringed instruments acting together opposing the keyboard or even sometimes subsidiary to the piano as an element in what is a piano dominated texture. Schumann’s First Piano Trio is the most often performed of his three trios and the one historians and commentators have agreed is the strongest of the three.

The first movement, Mit Energie und Leidenschaft (“with energy and passion”) is thoroughly expansive and passionate. Written in contrapuntal sonata form in the minor tonality, it begins with a fervent violin theme. As Arthur Cohn comments, “Schumann, a fully developed romanticist at age 37, would not have much, if any, proportions to his themes; they were now the almost non-adhering, tonally swerving type.” Cohn also notes that Schumann made this movement quite chromatic in a Romantic style. The pianist plays rapid arpeggios throughout the first section to emphasize the harmony. The cello echoes fragments of the main theme, in free imitation.

Since Schumann clearly wished to attain rhythmic variety, he immediately presented the principal theme in three slightly different versions. The opening theme is an example of his new style of composing in which, according to the Grove Dictionary of Music, he demonstrates the “simultaneous development of motivic combinations.” In the contrasting second theme, the pianist plays the melody together with the strings, and when the second theme repeats, the violin and cello play in canon two octaves apart, following each a half measure apart. Near the exposition’s end, the main theme reappears combined with fragments of the second. During the development, Schumann introduces a new theme that has a distinctive melodic character and unusual scoring. This theme appears softly in the piano’s high range; Schumann directs the accompanying strings to play “am Steg” which means bowing the string as close as possible to the bridge. After repeating the new theme a few times, Schumann reverts back to the two themes from the exposition. In the recapitulation, the passionate energy returns, and the theme from the development makes its hushed appearance, too. Clara thought that this movement was the most beautiful of all the chamber music movements that Schumann composed.

The second movement, Lebhaft, doch nicht zu rasch (“lively, but not too fast”), is a fiery Scherzo and Trio in F major. The strings have a melody that rises energetically with a sort of perky quality. Listeners can discern that the distinctive long-short rhythmic motive was foreshadowed in the first movement. The Trio section, smoothly legato, uses canonic imitation between the piano and the strings, recalling the canon in the second theme of the first movement. The trio and the scherzo themes are actually both based on the same motive. The Scherzo theme returns, and then the movement concludes with a coda. In the deeply expressive yet relatively somber and concentrated third movement, Langsam, mit inniger Empfindungen, (“slowly, with inner feeling”) Schumann creates an expressive melodic theme and gives the whole a ternary form. The theme has a limitless, searching, syncopated line that moves from instrument to instrument with the piano often providing a rich and sometimes chromatic chordal support. A short transitional passage in the piano leads directly into the major tonality of the vibrant and strongly optimistic sounding rondo finale, Mit Feuer, (“with fire”). Here Schumann unites the trio’s movements by giving the piano the first four notes from the violin theme of the first movement, but in the finale, these notes are rhythmically altered. As the energetic movement progresses, the thematic utterances modulate through a highly unusual variety of keys. The cello announces the movement’s second theme. In the development, Schumann gives half his attention to the first theme, while he devotes the other half to the second. He then presents a short recapitulation and a rather lengthy coda, which speeds up in tempo as it brings the quartet to its brilliant end.

© Susan Halpern, 2022

“Watching the trio perform, one really couldn’t tell who was happier to be there—the rapt audience or the musicians, who threw themselves into repertoire they clearly love.”

Aspen Times

“Excitement may be the best word to characterize the Junction Piano Trio.”

Lincoln Star Journal

Featured Artists

Videos

Jordan Hall Information

This performance is generously sponsored by

Susan & Michael Thonis.

Related Events

Evgeny Kissin, piano

2025 SHINE! Gala

Trio Oko

Featuring a Solo(s) Together world premiere by Reena Esmail

Samara Joy

Tessa Lark, Joshua Roman, Edgar Meyer

Stay in touch with Celebrity Series of Boston and get the latest.

Email Updates Sign up for Email Updates