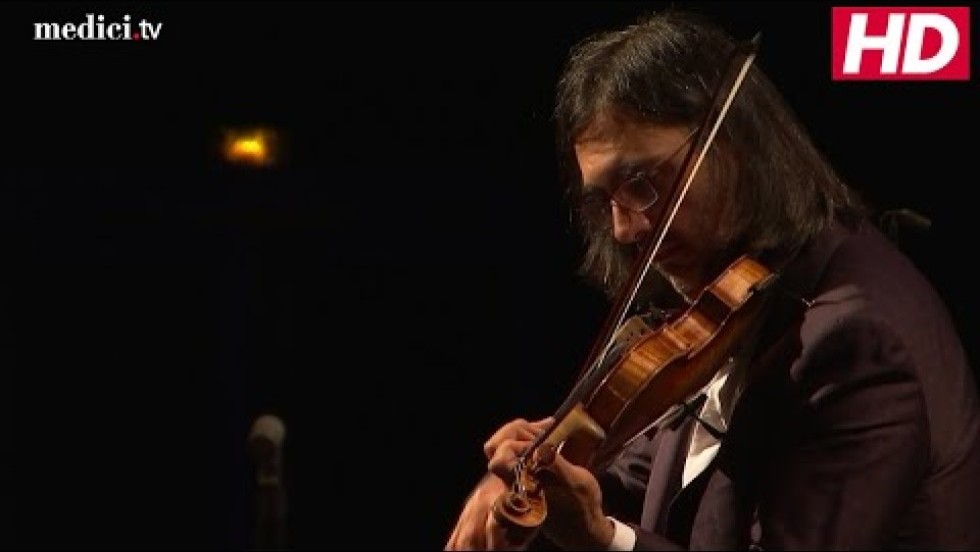

Leonidas Kavakos, violin

Daniil Trifonov, piano

Cookie Notice

This site uses cookies to measure our traffic and improve your experience. By clicking "OK" you consent to our use of cookies.

Two superstars join forces for a chamber recital spanning highlights of the piano and violin repertoire. Violinist Leonidas Kavakos makes a return to the Series for the first time since 2019, appearing with Daniil Trifonov for an evening of virtuosity highlighting 19th- and 20th-century classics from Beethoven, Bartók, and more.

Performance Program

The running time of this concert is approximately 95-100 minutes, including a 15-minute intermission between the Poulenc and Brahms sonatas

Beethoven wrote this sonata and the F-major Sonata No. 5, Op. 24, more or less simultaneously during 1800 and 1801. He originally intended that they be paired as Op. 23, nos. 1 and 2, but when the publisher’s engraver made the mistake of preparing some of the printing plates for them in different formats, the simplest way to deal with the problem was to make them into separate publications, Opp. 23 and 24. Beethoven dedicated them to Count Moritz von Fries, a wealthy Chamberlain at the Imperial Court, a banker, art collector, and music-lover who had probably commissioned them. Fries commissioned the C-major String Quintet, Op. 29, at about the same time, and it is dedicated to him. Beethoven became caught in an enormous tangle of lawsuits as a result of some liberties that Fries took with the publication rights, but by 1816, all was forgiven and the composer dedicated his Symphony No. 7 to the Count.

At a chamber music evening at Count Fries’ house in the spring of 1800, when Beethoven was beginning these sonatas, Daniel Steibelt (1765-1823), a composer trying to compete with Beethoven, decided to challenge Beethoven’s reputation as the best pianist in Vienna. One evening, just a week after hearing the variations in Beethoven’s Clarinet Trio at Fries’, Steibelt improvised on the same tune in a manner that was obviously intended to impress the company with the superiority of his skills. It soon became evident to everyone that his “improvisations” were not extemporaneously conceived. He had carefully prepared. Beethoven was furious. Beethoven picked up the cello part of a Steibelt quintet that was on the evening's program, put it on the piano’s music rack upside down, picked out a tune from it with one finger, and then improvised with such power and imagination that Steibelt left the room before Beethoven had finished. Steibelt’s reputation in Vienna was permanently damaged, and his next concert was a failure, but he did later succeed in one area where Beethoven had had a minor failure. Czar Alexander I, who never paid Beethoven for the dedication of the three violin sonatas, Op. 30, made Steibelt music director of his court in St. Petersburg in 1810.

The Sonata in A minor, Op. 23, is a great advance over its predecessors in several ways. Beethoven was then clearly at ease with his advanced musical ideas. The music does not strain for effect. Changing moods do not interrupt its flow. The complex counterpoint in parts of the unusual Presto first movement, which must have been so difficult to write, is easy and agreeable to the listening ear. This movement has been said to foreshadow the more famous “Kreutzer” sonata in its experimental nature. It is a quickly paced movement with so compact an exposition of its basic ideas that when Beethoven begins to develop these ideas, wholly new but related themes spill out of his imagination. Next comes an extraordinary middle movement, Andante scherzoso, più allegretto, a bright movement in a major tonality, that combines the contrasting functions of both slow movement and scherzo with the dramatic structure of the usual first-movement sonata-form. Returning to the minor home key again in the finale, Allegro molto, Beethoven presents the listeners with a free rondo with even more of the kind of counterpoint that enriched the first movement.

Beethoven wrote this sonata and the F-major Sonata No. 5, Op. 24, more or less simultaneously during 1800 and 1801. He originally intended that they be paired as Op. 23, nos. 1 and 2, but when the publisher’s engraver made the mistake of preparing some of the printing plates for them in different formats, the simplest way to deal with the problem was to make them into separate publications, Opp. 23 and 24. Beethoven dedicated them to Count Moritz von Fries, a wealthy Chamberlain at the Imperial Court, a banker, art collector, and music-lover who had probably commissioned them. Fries commissioned the C-major String Quintet, Op. 29, at about the same time, and it is dedicated to him. Beethoven became caught in an enormous tangle of lawsuits as a result of some liberties that Fries took with the publication rights, but by 1816, all was forgiven and the composer dedicated his Symphony No. 7 to the Count.

At a chamber music evening at Count Fries’ house in the spring of 1800, when Beethoven was beginning these sonatas, Daniel Steibelt (1765-1823), a composer trying to compete with Beethoven, decided to challenge Beethoven’s reputation as the best pianist in Vienna. One evening, just a week after hearing the variations in Beethoven’s Clarinet Trio at Fries’, Steibelt improvised on the same tune in a manner that was obviously intended to impress the company with the superiority of his skills. It soon became evident to everyone that his “improvisations” were not extemporaneously conceived. He had carefully prepared. Beethoven was furious. Beethoven picked up the cello part of a Steibelt quintet that was on the evening's program, put it on the piano’s music rack upside down, picked out a tune from it with one finger, and then improvised with such power and imagination that Steibelt left the room before Beethoven had finished. Steibelt’s reputation in Vienna was permanently damaged, and his next concert was a failure, but he did later succeed in one area where Beethoven had had a minor failure. Czar Alexander I, who never paid Beethoven for the dedication of the three violin sonatas, Op. 30, made Steibelt music director of his court in St. Petersburg in 1810.

The Sonata in A minor, Op. 23, is a great advance over its predecessors in several ways. Beethoven was then clearly at ease with his advanced musical ideas. The music does not strain for effect. Changing moods do not interrupt its flow. The complex counterpoint in parts of the unusual Presto first movement, which must have been so difficult to write, is easy and agreeable to the listening ear. This movement has been said to foreshadow the more famous “Kreutzer” sonata in its experimental nature. It is a quickly paced movement with so compact an exposition of its basic ideas that when Beethoven begins to develop these ideas, wholly new but related themes spill out of his imagination. Next comes an extraordinary middle movement, Andante scherzoso, più allegretto, a bright movement in a major tonality, that combines the contrasting functions of both slow movement and scherzo with the dramatic structure of the usual first-movement sonata-form. Returning to the minor home key again in the finale, Allegro molto, Beethoven presents the listeners with a free rondo with even more of the kind of counterpoint that enriched the first movement.

Francis Poulenc belonged to a group of French composers, which also included Milhaud and Honegger, who in 1920 were dubbed “The Six.” This group helped to turn French music away from stultifying formality, elevated pretense, and empty pomp.

Poulenc’s most widely known chamber music involves wind instruments, not strings. He discarded two violin sonatas before he composed this one, which was a long time in reaching its final form. He originally wrote this sonata in 1942 and 1943 for the magnificent young French violinist Ginette Neveu, who lost her life in a plane crash at the age of thirty, in 1949. Poulenc decided to revise the sonata in that year; he particularly made many changes in the last movement. The sonata recalls the composer’s memory of the great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1899-1936), who was shot by the Fascist Falangists soon after the outbreak of civil war in his country.

This Romantic and melodic work is infused with tragedy that is expressed in the opening Allegro con fuoco in a musical language related to that of the best-known French sonata, one by César Franck. Poulenc headed his second movement, Intermezzo, with a quotation from García Lorca, “The guitar makes dreams weep,” an allusion to the poet’s own guitar arrangements of Spanish folk and popular songs. The third movement carries the uncommon indication, Presto tragico, calling for a very quick beat but a tragic mood. The sonata progresses lyrically, yet speedily, to its close.

Francis Poulenc belonged to a group of French composers, which also included Milhaud and Honegger, who in 1920 were dubbed “The Six.” This group helped to turn French music away from stultifying formality, elevated pretense, and empty pomp.

Poulenc’s most widely known chamber music involves wind instruments, not strings. He discarded two violin sonatas before he composed this one, which was a long time in reaching its final form. He originally wrote this sonata in 1942 and 1943 for the magnificent young French violinist Ginette Neveu, who lost her life in a plane crash at the age of thirty, in 1949. Poulenc decided to revise the sonata in that year; he particularly made many changes in the last movement. The sonata recalls the composer’s memory of the great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1899-1936), who was shot by the Fascist Falangists soon after the outbreak of civil war in his country.

This Romantic and melodic work is infused with tragedy that is expressed in the opening Allegro con fuoco in a musical language related to that of the best-known French sonata, one by César Franck. Poulenc headed his second movement, Intermezzo, with a quotation from García Lorca, “The guitar makes dreams weep,” an allusion to the poet’s own guitar arrangements of Spanish folk and popular songs. The third movement carries the uncommon indication, Presto tragico, calling for a very quick beat but a tragic mood. The sonata progresses lyrically, yet speedily, to its close.

In his first twenty years, Johannes Brahms made an astonishing leap from a miserable childhood in the downtrodden harbor area of Hamburg to an eminent position as a distinguished young composer. He began his career as a musician at the age of twelve by giving piano lessons for pennies, and at thirteen, he was playing in harborside sailors’ bars. By the age of sixteen, however, he had progressed to playing Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata as well as one of his own compositions in a public concert. In April 1853, just before his twentieth birthday, he set out from Hamburg on a modest concert tour, traveling mostly on foot. In Hanover, he called on the violinist Joseph Joachim, who, at twenty-two, had just become the head of the royal court orchestra there. Joachim was so impressed by Brahms that he gave him a letter of introduction to Liszt in Weimar and sent him to see Schumann in Düsseldorf. Robert Schumann was then Germany’s leading composer, and his wife, Clara, was one of Europe’s greatest pianists. When the Schumanns heard Brahms play, they invited him to their home.

Although this sonata purports to be Brahms’s first sonata for violin and piano, according to the reflections of a student of Brahms, the composer discarded five violin sonatas that he had composed before he wrote this one, the first that he thought good enough to preserve and present to the world. He wrote this sonata during the summers of 1878 and 1879, when he had already become a mature artist. It was his only piece of chamber music from the productive period in which he composed his Symphony No. 2, the “Academic Festival” and “Tragic” overtures, the violin concerto and the second piano concerto.

This sonata, like the Violin Concerto, Op. 77, owes a great deal to Joachim as well as to Clara Schumann, who by then was a widow. Clara was a distinguished pianist and composer in her own right. When Brahms sent Clara a manuscript of this new work, she wrote back, “I must send you a line to tell you how excited I am about your Sonata. It came today. Of course, I played it through at once, and at the end could not help bursting into tears of joy.” Ten years later, when Clara was seventy years old and in failing health, she still loved the sonata and treasured the friendship of both Joachim and Brahms. From her house in Frankfurt she wrote a touching letter to Brahms, in which she said, “Joachim was here on Robert’s eightieth birthday and we had a lot of music. We played the [Op. 78] Sonata again and I reveled in it. I wish that the last movement could accompany me in my journey from here to the next world.”

This sonata is one of the most lyrical compositions among all of Brahms’ instrumental works. The violin always has the leading voice, and the piano writing is always so clear and transparent that an imbalance never exists between the two instruments. There are only three movements, not the usual four frequently considered traditional for a sonata. Brahms wrote to his publisher, clearly in jest, that since he came up one movement short, he would, therefore, accept 25% less than his usual fee for this work.

As in many of Brahms’ compositions, the movements are intimately interrelated. A three-note motto figure is common to all three movements. A mood of gentle nostalgia permeates the first movement, Vivace ma non troppo, and sets the tone and character for the entire sonata. Brahms here works much like Beethoven had before him: he introduces a germ out of which themes for the whole movement will eventually evolve and grow. The second movement is a solemn and dramatic Adagio, and the third, a rondo, Allegro molto moderato, contains an episode in which Brahms brings back the slow movement theme. The principal melodic material of this movement, however, comes from a related pair of his songs, “Regenlied” (“Rain Song”) and “Nachklang” (“Reminiscence”), Op. 59, nos. 3 and 4.

In his first twenty years, Johannes Brahms made an astonishing leap from a miserable childhood in the downtrodden harbor area of Hamburg to an eminent position as a distinguished young composer. He began his career as a musician at the age of twelve by giving piano lessons for pennies, and at thirteen, he was playing in harborside sailors’ bars. By the age of sixteen, however, he had progressed to playing Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata as well as one of his own compositions in a public concert. In April 1853, just before his twentieth birthday, he set out from Hamburg on a modest concert tour, traveling mostly on foot. In Hanover, he called on the violinist Joseph Joachim, who, at twenty-two, had just become the head of the royal court orchestra there. Joachim was so impressed by Brahms that he gave him a letter of introduction to Liszt in Weimar and sent him to see Schumann in Düsseldorf. Robert Schumann was then Germany’s leading composer, and his wife, Clara, was one of Europe’s greatest pianists. When the Schumanns heard Brahms play, they invited him to their home.

Although this sonata purports to be Brahms’s first sonata for violin and piano, according to the reflections of a student of Brahms, the composer discarded five violin sonatas that he had composed before he wrote this one, the first that he thought good enough to preserve and present to the world. He wrote this sonata during the summers of 1878 and 1879, when he had already become a mature artist. It was his only piece of chamber music from the productive period in which he composed his Symphony No. 2, the “Academic Festival” and “Tragic” overtures, the violin concerto and the second piano concerto.

This sonata, like the Violin Concerto, Op. 77, owes a great deal to Joachim as well as to Clara Schumann, who by then was a widow. Clara was a distinguished pianist and composer in her own right. When Brahms sent Clara a manuscript of this new work, she wrote back, “I must send you a line to tell you how excited I am about your Sonata. It came today. Of course, I played it through at once, and at the end could not help bursting into tears of joy.” Ten years later, when Clara was seventy years old and in failing health, she still loved the sonata and treasured the friendship of both Joachim and Brahms. From her house in Frankfurt she wrote a touching letter to Brahms, in which she said, “Joachim was here on Robert’s eightieth birthday and we had a lot of music. We played the [Op. 78] Sonata again and I reveled in it. I wish that the last movement could accompany me in my journey from here to the next world.”

This sonata is one of the most lyrical compositions among all of Brahms’ instrumental works. The violin always has the leading voice, and the piano writing is always so clear and transparent that an imbalance never exists between the two instruments. There are only three movements, not the usual four frequently considered traditional for a sonata. Brahms wrote to his publisher, clearly in jest, that since he came up one movement short, he would, therefore, accept 25% less than his usual fee for this work.

As in many of Brahms’ compositions, the movements are intimately interrelated. A three-note motto figure is common to all three movements. A mood of gentle nostalgia permeates the first movement, Vivace ma non troppo, and sets the tone and character for the entire sonata. Brahms here works much like Beethoven had before him: he introduces a germ out of which themes for the whole movement will eventually evolve and grow. The second movement is a solemn and dramatic Adagio, and the third, a rondo, Allegro molto moderato, contains an episode in which Brahms brings back the slow movement theme. The principal melodic material of this movement, however, comes from a related pair of his songs, “Regenlied” (“Rain Song”) and “Nachklang” (“Reminiscence”), Op. 59, nos. 3 and 4.

xx

xx

Videos

“Kavakos is one of those soloists who makes the seemingly impossible sound as natural as breathing.... no technical difficulties fazed him, not even the demand for pin-point intonation in the high registers. The applause was vociferous… ”

Bachtrack

“[Daniil Trifonov] showed off a Romantic temperament to go with intelligence, imagination, tone, and a fabulous technique. It made for a riveting evening… ”

The Boston Globe

Featured Artists

Symphony Hall Venue Information

This performance is made possible in part by support from Celebrity Series' LIVE PERFORMANCE! Arts for All Endowment Funds, with generous leadership support from

Eleanor & Frank Pao.

Related Events

Evgeny Kissin, piano

Stay in touch with Celebrity Series of Boston and get the latest.

Email Updates Sign up for Email Updates