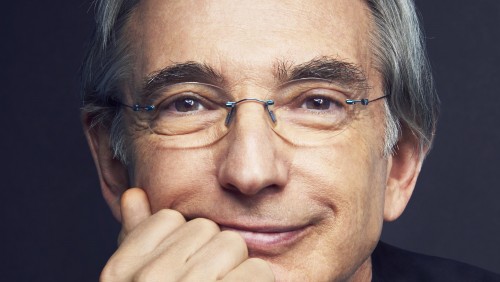

San Francisco Symphony; Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor; Christian Tetzlaff, violin soloist

Cookie Notice

This site uses cookies to measure our traffic and improve your experience. By clicking "OK" you consent to our use of cookies.

The acclaimed San Francisco Symphony return for their eighth Celebrity Series appearance, their final under the baton of visionary music director Michael Tilson Thomas, who has announced his retirement in 2020. The program features “an artist who considers the ordinary unacceptable” (New York Times), the brilliant German violinist Christian Tetzlaff – who has more recently dazzled audiences in recital and chamber performances – in his first Series performance in more than 25 years as an orchestral soloist.

Program

Michael Tilson Thomas Agnegram

Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Opus 64

Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, “Eroica”

Runtime: approximately 100 minutes with intermission.

Prices, seating sections, and programs are subject to change.

“In San Francisco, I’ve been lucky to find colleagues who say, ‘Sure, let’s try it. Does it feel more comfortable? Can we do something creative and interesting with this?' I’ve been here 25 years, and my relationship with the orchestra, the kinds of things we talk about, is at its height, I feel. I’m so appreciative of that.”

Michael Tilson Thomas, to David Weininger The Boston Globe

Artist Videos

Artist Websites

Sponsored by

Additional support provided by the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, Boston

This concert is made possible in part by support from the LIVE PERFORMANCE! Arts for All Endowment & Innovation Funds with generous leadership support from Eleanor & Frank Pao and Susan & Michael Thonis.

Notes on the Program

Michael Tilson Thomas (b.1944)

Agnegram, for large orchestra (1998)

Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT) on Agnegram:

Agnegram was written to celebrate the 90th birthday of the San Francisco Symphony's extraordinary patron and friend Agnes Albert, and is a portrait of her sophisticated and indefatigably enthusiastic spirit. It is entirely composed of themes derived from the spelling of her name.

A—G—E are obviously the notes that they name. B is B-flat (as this note is called in German). S is E-flat, also a German musical term. T is used to represent one note, B-natural, the “ti” of the solfège scale. From these arcane but not unprecedented manipulations (Bach, Schumann, and Brahms among others often did this kind of thing), a basic “scale” of eight unusually arranged notes emerges, from which all the themes are drawn. The piece itself is a march for large orchestra. The first part of the march is in 6/8 and is almost a mini-concerto for orchestra, giving brief sound-bite opportunities for the different sections of settling into a jazzy and hyper-rangy tune.

The middle section of the march, or trio, is in 2/4 and settles into a kind of sly circus atmosphere. Different groups of instruments in different keys make their appearance in an aural procession. First, the winds in C play a new march tune saying “Agnes Albert.” Then, the instruments in F are heard playing the same tune. But as these instruments are transposing instruments, although the notes they play read A—G—N—E—S etc., the notes that are heard are completely different. They are followed by instruments in E-flat and B-flat until quite a jungle-like cacophony is built up—punctuated by alternately elegant and goofball percussion entrances. The jazzy 6/8 tune reappears now in canon and the piece progresses to a jubilant and noisy ending.

MTT on his revision for the San Francisco Symphony’s 2016 Asia Tour:

Agnegram was originally written around the musical letters/notes that are a part of Agnes Albert's name. There are seven of them, which makes the piece septatonic. Perhaps the fact that a septatonic scale contains a pentatonic scale—the most commonly used scale in Asian music—prompted me to think about exploring more of those possibilities before we took the piece on our 2016 Asia Tour.

This piece is still in the form of a march. But now the middle section, a kind of John Philip Sousa-like trio, explores a musical joke that I had planned, but not finished in time, for the premiere performance. The trio recalls many famous tunes that amused Agnes. There are surreal references to Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Irish lullabies, but they appear only to the degree that the notes that they have in common with her name will allow.

I think she would have enjoyed discovering them and chuckling over them.

—Michael Tilson Thomas

© 2019. San Francisco Symphony

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Concerto in E minor for violin and orchestra, Opus 64 (1844)

Ferdinand David was the first violinist to play the Mendelssohn Concerto, but more important, the work was intended for him from the beginning. David and Mendelssohn had been friends since 1825 and the violinist was held in the highest regard as soloist, as a model concertmaster, as quartet leader, and teacher. Mendelssohn’s Concerto is in fact the first in the distinguished series of violin concertos written by pianist-composers with the assistance of eminent violinists.

Across a backdrop of quietly pulsating drums and plucked basses, the violin sings a famous melody. The first extended passage for the orchestra is dramatically introduced by the boldly upward-thrusting octaves of the violin; it also gives way quickly to the next solo, a new melody, full of verve, and barely begun by the orchestra before the soloist makes it his own. The violin dazzles us with brilliant passage work, and that is what Mendelssohn really means us to pay attention to, but at almost any moment in which you choose to listen to what is going on “behind,” you will be rewarded by real activity, not just mechanical strumming. It is as though solo and tutti both managed to be foreground and background at the same time.

The theme that brings the first big change of character is deliciously scored. The violin has made a graceful landing on its lowest G after a descent of more than three octaves, and it is over that quiet, sustained, and solitary sound of the G that the clarinet (with another clarinet and a pair of flutes) introduces the new tune. The presentation is immediately reversed, with the violin playing the melody and the four winds accompanying. Either way, the combination of wind quartet with a single stringed instrument is wonderfully fresh.

The first movement cadenza is famous. In Classical practice, the cadenza occurs at the joint of recapitulation and coda. Mendelssohn uses it instead at the other crucial harmonic juncture, the recapitulation, the return to the home key after the peregrinations of the development. He prepares this homecoming subtly, allowing himself some delicate anticipations of what it will be like to be in E minor again, managing this maneuver as a gradual subsidence of wonderful breadth and serenity. On the doorstep of home, the orchestra stops and defers to the soloist.

A couple of years earlier, in his Scottish Symphony, Mendelssohn experimented with the idea of going from movement to movement without a break. Here he takes the plan a step further, not merely eliminating the pauses but actually constructing links. The Andante emerges mysteriously from the close of the first movement. This could be one of Mendelssohn’s songs (with or without words). It is a lovely and sweet melody of surprising extension, beautifully harmonized and scored. Listen to the effect, for example, of the woodwinds in the few measures in which they participate. The middle section brings an upsurge of passion and a return to the minor mode. Then the first melody returns, still more beautifully set than before, with the accompanying instruments unable to forget the emotional tremors of the movement’s central section.

Between the Andante and the finale Mendelssohn places another kind of bridge, a tiny and wistful intermezzo. Strings only accompany the violin, which sets off nicely the touch of fanfare that starts the finale. It is sparkling and busy music whose gait allows room for swinging, broad tunes, as well as for the dazzling sixteenth notes of the solo part. Here, too, Mendelssohn delights in the witty play of foreground and background, and so he steers the concerto to its close in a feast of high spirits and with a wonderful sense of “go.”

—Michael Steinberg

Program notes © 2019. San Francisco Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Opus 55 “Eroica” (1804)

In May 1804, Napoleon, who had been acceptable to Beethoven as a military dictator as long as he called himself First Consul, had himself crowned Emperor, and the disappointed and angry composer scratched out the words “intitolata Bonaparte” on the title page of his newly completed symphony. Actually, Beethoven blew hot and cold on that issue. In August of that same year, he told the publishing firm of Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig that this symphony “is really called ‘Ponaparte’ [sic].” At some point, too, Beethoven penciled the words “Geschrieben auf Bonaparte” (“Written on Bonaparte”) on that mutilated title page. But the score of the Third Symphony as printed in October 1806 tells us that this is a sinfonia eroica, a “heroic symphony . . . composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

“I’ll pay another Kreuzer if the thing will only stop,” a gallery wit called out at the public premiere of the Eroica in 1805. One critic conceded that in this “tremendously expanded, daring, and wild fantasia” there was no lack of “startling and beautiful passages in which the energetic and talented composer must be recognized,” but he felt that the work “loses itself in lawlessness.” Beethoven had given his audience plenty to be upset about—a symphony half again as long as any they would have known, and one unprecedented in demands on orchestral virtuosity that were almost certainly inadequately met, unprecedented as well in the complexity of its polyphony, in the unbridled force of its rhetoric, in the weirdness of details like the famous “wrong” horn entrance in the first movement (the horn has already reached the home chord of E-flat while the violins are still preparing its arrival with a dissonance), and with procedures so radical as the disintegration of the theme at the end of the monumental Funeral March.

Another newness in the Eroica is the shift of the center of gravity from the first movement to the Finale. Facing a new challenge, Beethoven turned to old music; that is, he made a set of variations on a theme he had first used in a group of contradances in 1800-01, which he had introduced at about the same time in the finale of his ballet The Creatures of Prometheus, and which had also yielded Fifteen Variations and a Fugue for Piano in 1802. In the symphony, he provides a grand, rhetorical introduction or “frame.” After the witty exploration of the possibilities of the bass alone comes a powerful set of variations on the combined melody and bass. In the Piano Variations he had wrapped it all up with a fugue. Now he does something subtler: instead of making his excursion into polyphonic style a separate chapter, he infuses his variations with polyphony throughout their course. The vitality of texture that this gives him is one of the chief sources of the propulsive energy of the movement. True to classical tradition for variations, Beethoven slows the tempo near the end. The slow variations here are an apotheosis, a climax of towering force. Carefully Beethoven dismantles this structure: the music is almost an echo of the “disintegration” of the Funeral March. Then he resumes speed to close, to fulfill his “heroic symphony” in triumphantly affirmative noise.

—Michael Steinberg

Program notes © 2019 San Francisco Symphony

Stay in touch with Celebrity Series of Boston and get the latest.

Email Updates Sign up for Email Updates